This is part two in a series on Gary Ng, Bridging Finance and the web that interconnects them. To read part one, click here.

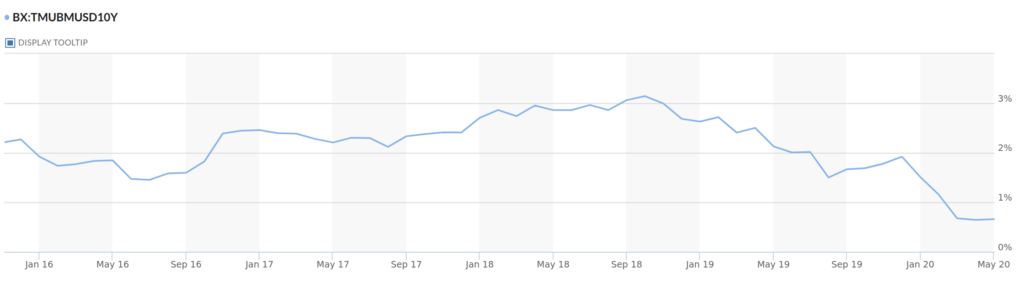

From 2016 through 2020, the yield on the benchmark 10 year US Treasury Note peaked at 3.026%, and averaged somewhere around 2.5%.

A low rate environment like that is a lot of fun for stock pickers, but it’s tough sledding for the rate junkies. To income investors, trading stocks might as well be taking their money to the dog track. They’re interested in interest, and with Treasuries yielding 2.5%, and S&P dividends yielding even less (~2%), there wasn’t a lot of options out there for investors whose models needed a payout.

The low rates were doing their macroeconomic job, though, and putting a tailwind behind the country’s economic growth. Caught in an eddy of that tailwind were Canadian medium and mid-market businesses; generally too small to float their debt on a corporate market, and often in need of more money than the bank could lend. So, along came Bridging Financial, engineering a bridge between the capital markets and these mid-sized businesses with beautiful, pure, efficient capitalism.

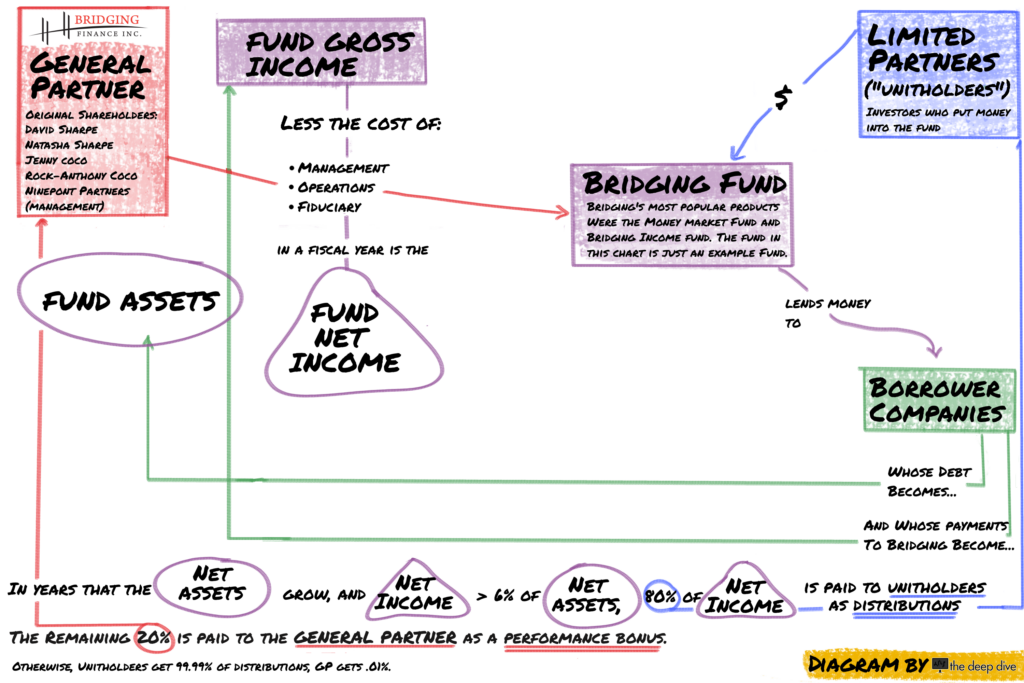

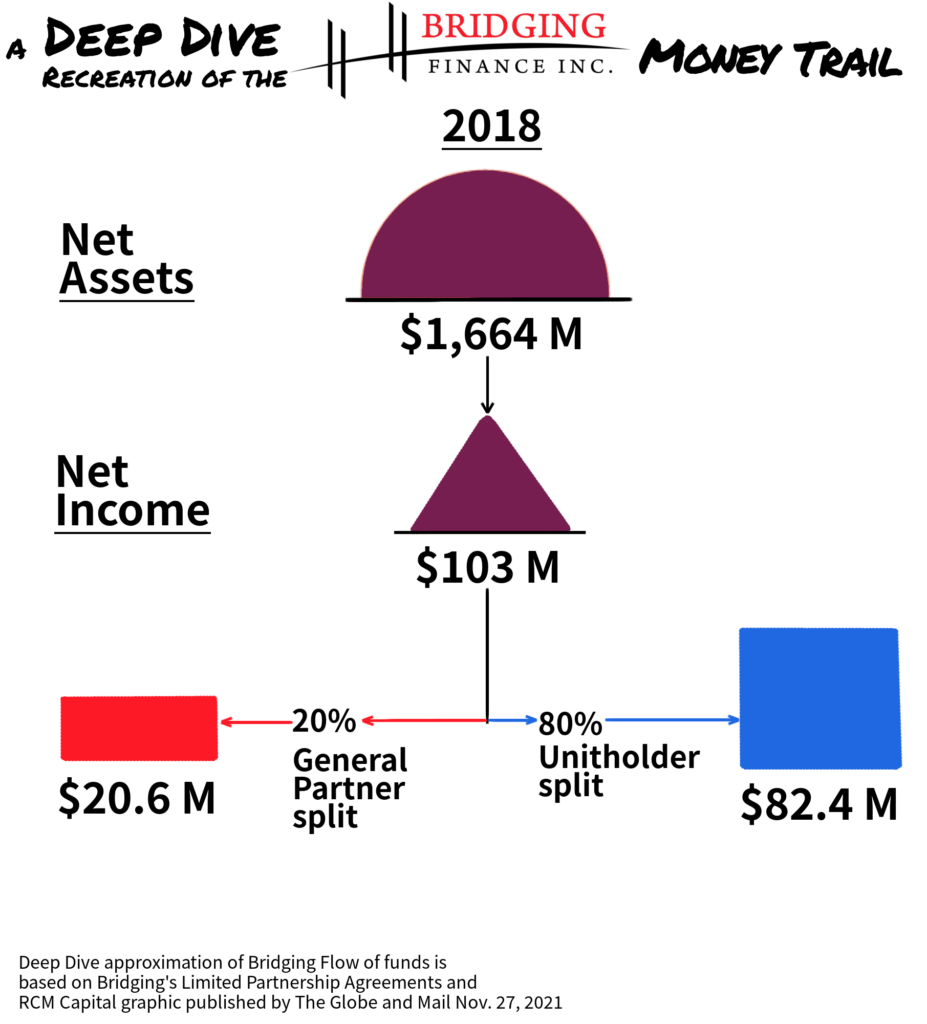

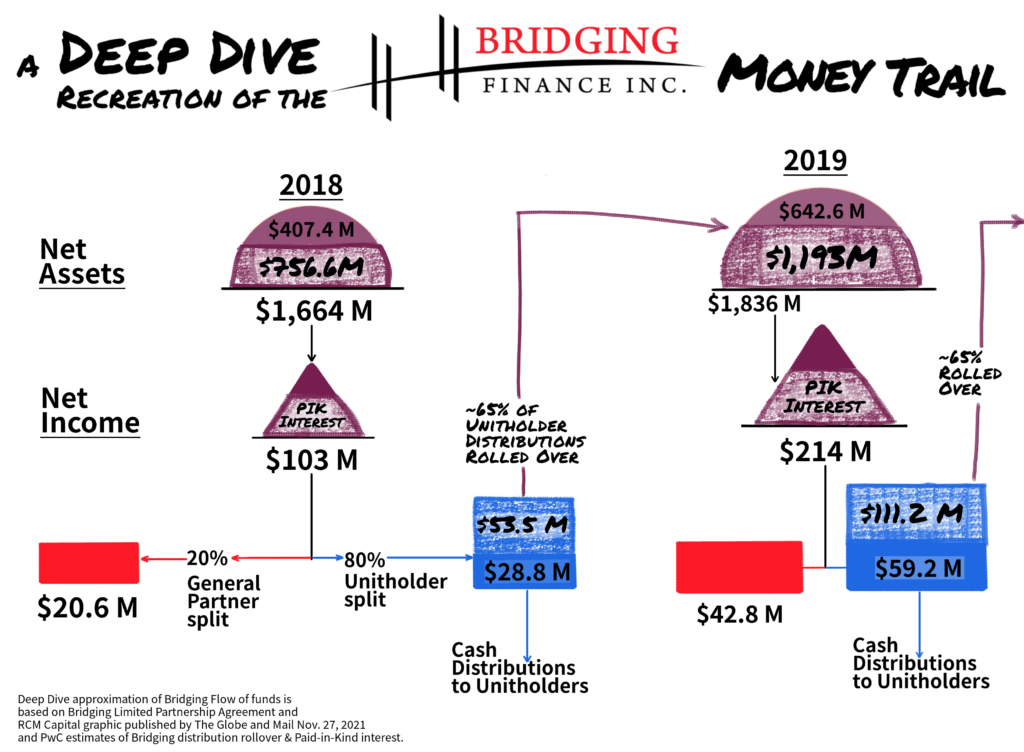

Bridging was run by husband and wife team David and Natasha Sharpe, who co-founded it with Jenny and Rocky Coco, the brother and sister principles of Coco Paving Inc. It sold investments in Limited Partnership structures designed to make high interest loans to those mid-sized businesses, then used the income from those loans to generate a return for the Limited Partners; the unitholders. The General Partner (Bridging Finance) was paid based on performance, earning 20% of the funds’ net income in years that the funds earned more than the 6% hurdle rate.

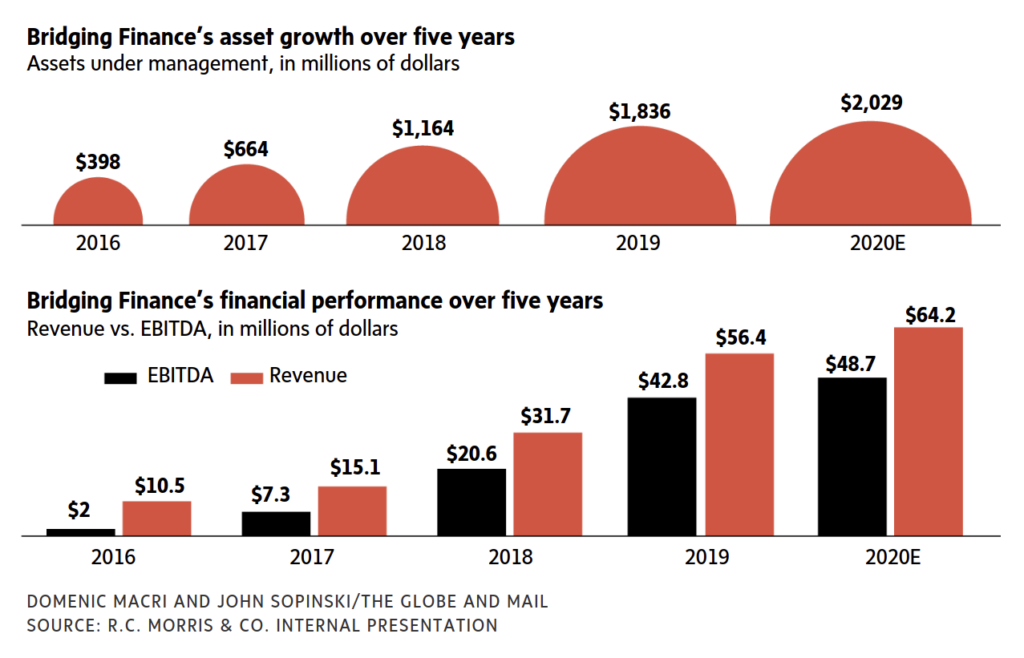

The products were a big hit with income investors, who were quite happy to give up 20% of that sweet, sweet yield to a manager who could deliver it at 6%+. Bridging’s income fund products were marketed by Sprott Securities at first, and the products grew steadily, always hitting their hurdle rates, always paying fat redemptions.

Mid market lenders charge borrowers high interest rates for a reason. Businesses that generate significant cash flows don’t often need to leverage their balance sheets, and the ones with low cash flow tend to have trouble making payments. The high interest rate is usually the way the lender comes away with a decent return despite a high rate of default. But the partners at Bridging are talented financial engineers, who pioneered a method of portfolio construction that turned the high risk borrowers most likely to default into the NAV growth and net income that they needed to hit their performance targets.

Bridging had a habit of allowing its borrowers to make the interest payments on their loans in kind (PIK). In some cases the borrowers were allowed to make payments in company equity, and in other cases were just allowed to compound the interest owing onto the outstanding principle as an accrual. A lending outfit playing by the rules would have considered debt that the borrowers couldn’t make cash payments on to be distressed debt, and written it down if the company didn’t have collateral that could be appropriated, but those outfits aren’t bold, modern, innovative financial engineers.

The aggressive and whimsical growth projections that we were used to seeing in the Canadian cannabis boom made cannabis co’s prime targets for Bridging Finance loans. The financial statements of the two cannabis co’s we know took loans show these debts being warehoused, expanded and bounced around balance sheets, expanding the Bridging assets under management, and tucking away dead loans that could sink them or sandbag the return.

The interest on Bridging loans to cannabis company MJardin was almost entirely paid-in-kind. Bridging’s receivers recently issued a demand notice for $177 million in outstanding debt. The company never produced more than $7.6 million in income in a quarter.

Harvest Health and Recreation, comparatively, had $145.8 million worth of debt to Bridging on its balance sheet when it was taken over by Trulieve this past October.

More on both those stories in parts three and four.

As many of the loans went bad, Bridging appears to have warehoused them on the books of an… ambitious venture, undertaken by one Sean McCoshen, that aimed to build a railway from Alberta to Alaska. The project is now bankrupt.

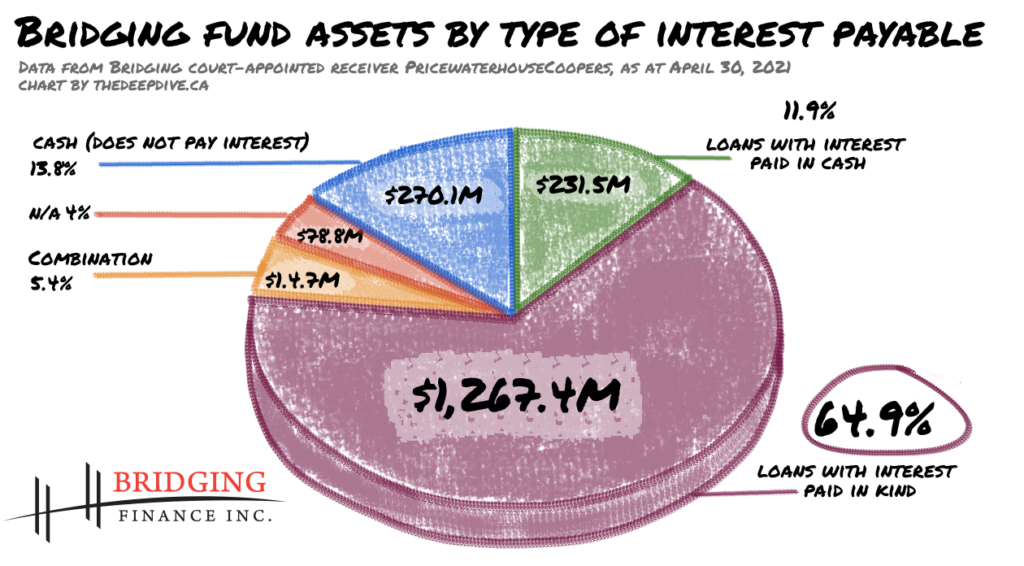

Not all of the details of the Bridging loan portfolio are available to us. A very detailed affidavit that made it into the receivership filings has been redacted to remove the exhibits that lay out who borrowed all of this money, but the receivers’ reports give a good global overview of what was left in April of 2021.

As of April 30, 2021, $1.7 billion of the $1.9 billion in outstanding Bridging loans were accruing interest paid-in-kind. The largest eleven PIK loans had a book value of $952 million, $213 million of which consisted of accrued interest.

One might expect all of that paid in kind interest to catch up with the fund at redemption time, but the rate-junky archetype unitholders allowed Bridging to engineer a counterbalance.

An income investor that finds a steady payout is likely to re-invest that payout to grow the principal, creating more distributions that they can re-invest, etc. These income guys are fiends for compounding. Bridging’s funds were set up to re-invest unitholder distributions automatically. PwC reports that 65% of Bridging’s unitholders took their monthly distributions in-kind, rolling them over into more units in the fund, instead of taking them in cash.

The in-kind distributions are enough to carry the in-kind interest for a while, but any good engineer knows that no structure is permanent. The Sharpes & CoCos’ original partners in Bridging Finance was a Sprott Securities-affiliated company called Ninepoint, which handled the marketing and administration of the funds. Ninepoint was bought out of its position by the other partners in October of 2018, after Ninepoint threatened litigation over an apparent misappropriation of funds.

That left the Sharpes & CoCos in sole possession of an income fund hiding the fact that most of its income was non-cash, by paying distributions that were also mostly non-cash. The cash payments the Sharpes had been known to take from loan recipients wasn’t making matters any better. What they needed was some liquidity, preferably in the form of a willing partner, ready to buy equity in the general partner.

But who would want to buy a part of Bridging after doing basic due diligence on the loan portfolio? It would have to be someone who wasn’t going to look too carefully. Someone more concerned with owning it than understanding what it is…

…someone like Gary Ng.

Ng had been around Bridging since 2018, borrowing against Chippingham assets to expand it through acquisitions. Bridging was quite accommodating, allowing for him to roll interest over and never defaulting. $27.6 million was still outstanding on the original $20.3 million loan in 2020.

All told, the Bridging Funds lent Ng and his holding companies a total of $119 million in this mess, but the relevant sum here is the the $67 million that Bridging lent him while they were negotiating to sell him a 50% stake in the general partner. Bridging officials told the OSC that the money was for something else entirely, and they didn’t see a problem with loaning him money to take half of this commercial lender with developing liquidity problems off their hands.

To say the Sharpes would soon learn that Ng’s collateral wasn’t what they expected it to be is giving them too much credit for naivete. It’s likely they knew all along and just didn’t care. What they would soon learn, is that Ng wasn’t careful enough to keep the fake a secret.

More to come…

Information for this story was found via the Globe and Mail, BNN Bloomberg and the other sources mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Views expressed within are solely that of the author. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.