Cruise, a subsidiary of General Motors, faces its own set of safety concerns as it works on autonomous vehicles. It is grappling with regulatory backlash, concerned employees, and doubts about both Vogt’s leadership and the feasibility of a business that has been touted as a lifesaver and a billion-dollar enterprise.

On October 2, an incident occurred when a car struck a woman at a San Francisco intersection, propelling her into the path of one of Cruise’s autonomous taxis. The Cruise vehicle ran over the woman, momentarily halted, and then dragged her for approximately 20 feet before coming to a stop at the curb, causing severe injuries.

The California Department of Motor Vehicles recently accused Cruise of omitting the dragging part of the woman’s ordeal from a video initially provided to the agency. The DMV stated that the company had “misrepresented” its technology and ordered Cruise to halt its autonomous car operations in the state.

Two days later, Cruise voluntarily suspended all driverless operations across the country, taking around 400 autonomous cars off the roads. Subsequently, Cruise’s board engaged the services of the law firm Quinn Emanuel to conduct an investigation into the company’s response to the incident. This inquiry encompasses interactions with regulators, law enforcement, and the media. Exponent, a consulting firm specializing in complex software systems, is also conducting a separate review of the crash.

This comes nearly two months after Kyle Vogt, CEO of Cruise, seemed to be a bit emotional when he recounted a tragic incident that had recently occurred in San Francisco. A driver had struck and killed a 4-year-old girl in a stroller at an intersection. “It barely made the news,” he said, his voice wavering. “Sorry. I get emotional.”

In a recent interview, Vogt stressed that the key to safer streets lies in embracing self-driving cars, such as those designed by Cruise. He emphasized that these autonomous vehicles do not succumb to distractions, drowsiness, or intoxication. Their primary objective is safety, and Vogt believed they could significantly reduce car-related fatalities.

Speed vs. safety

Inside Cruise, employees express concerns about the challenges faced by the company, with some believing there may be no straightforward solutions. Simultaneously, Cruise’s competitors are wary of the fallout from its issues, as stricter regulations on driverless cars could impact the entire industry.

Many within the company attribute the problems to a tech industry culture led by 38-year-old Vogt, which prioritized speed over safety. In the rivalry between Cruise and its chief driverless car competitor, Waymo, Vogt aimed to dominate the market, much like Uber did with its smaller ride-hailing rival, Lyft.

During a companywide meeting on Monday, Vogt addressed the suspended operations, indicating that he did not have a clear timeline for when they might resume and hinting at possible layoffs, according to two employees who attended the meeting. He acknowledged that Cruise had lost the public’s trust and outlined a plan to rebuild it through increased transparency and a stronger emphasis on safety. Louise Zhang, the vice president of safety, was appointed as the company’s interim chief safety officer, reporting directly to Vogt.

“Trust is one of those things that takes a long time to build and just seconds to lose,” Vogt emphasized during the meeting. “We need to get to the bottom of this and start rebuilding that trust.”

Vogt’s journey in the self-driving car industry began during his teenage years, when he programmed a Power Wheels ride-on toy car to follow a yellow line in a parking lot at the age of 13. He later participated in a government-sponsored self-driving car competition while studying at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

In 2013, he founded Cruise Automation, a company that retrofitted conventional cars with sensors and computers to operate autonomously on highways. Three years later, he sold the business to General Motors for $1 billion.

Following the acquisition, Dan Ammann, General Motors’ president, assumed the role of Cruise’s CEO, with Vogt becoming its president and chief technology officer. In his capacity as president, Vogt expanded Cruise’s engineering team, and the company’s workforce grew from 40 to about 2,000 employees. He was dedicated to rapidly expanding the company into as many markets as possible, believing that speed was crucial in saving lives.

In 2021, Vogt took the reins as Cruise’s chief executive, and he began participating in earnings calls and presentations alongside Mary T. Barra, General Motors’ CEO. During these sessions, Vogt touted the self-driving market and projected that Cruise would have one million cars on the road by 2030.

Vogt continued to push for aggressive expansion, learning from past incidents involving Cruise vehicles operating in San Francisco. The company charged an average of $10.50 per ride in the city.

The mounting regulatory pressure

Last summer, after a Cruise vehicle collided with a Toyota Prius in a bus lane, some employees proposed temporarily avoiding streets with bus lanes. However, Vogt vetoed the idea, emphasizing the need for Cruise’s vehicles to navigate these streets to master their complexity. The company later modified its software to reduce the risk of similar accidents.

In August, a Cruise autonomous car collided with a San Francisco fire truck responding to an emergency. Subsequently, the company altered its cars’ ability to detect sirens.

However, following the recent crash and mounting pressure from city officials and activists, there were calls for Cruise to slow its expansion and provide more comprehensive data on collisions, unplanned stops, traffic violations, and vehicle performance. Aaron Peskin, president of San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors, expressed concerns about Cruise’s corporate behavior eroding public trust.

With Cruise’s operations halted, there are concerns that the company may be posing a financial burden on General Motors and tarnishing the auto giant’s reputation. Just hours before the California DMV ordered the suspension of Cruise’s driverless operations, GM’s CEO, Mary T. Barra, had expressed optimism about Cruise’s growth prospects.

For over a week, Cruise has not been collecting fares or transporting riders in San Francisco, Phoenix, Dallas, Houston, Miami, and Austin, Texas. The shutdown presents challenges to Cruise’s goal of achieving $1 billion in revenue by 2025.

General Motors has spent an average of $588 million per quarter on Cruise in the past year, representing a 42 percent increase from the previous year. According to an insider, each Chevrolet Bolt used by Cruise costs between $150,000 and $200,000.

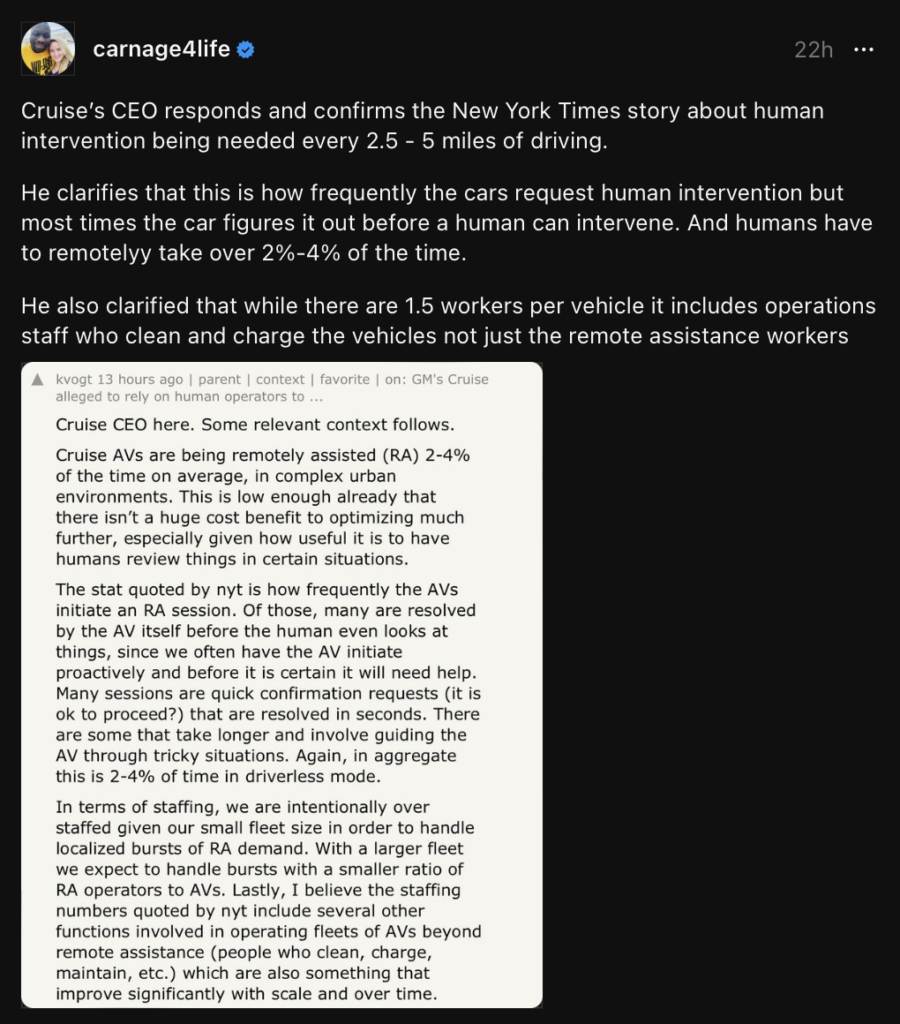

At the time of the suspension, half of Cruise’s 400 vehicles were in San Francisco, supported by a substantial operations staff. These employees intervened every 2.5 to 5 miles to remotely control the vehicles when issues arose, frequently making adjustments based on cellular signals.

In what seems to be a response to the issue, Vogt clarified that Cruise’s autonomous vehicles (AVs) are “being remotely assisted (RA) 2-4% of the time on average,” adding that this low enough already that there isn’t a huge cost benefit to optimizing much further, especially given how useful it is to have

humans review things in certain situations.

“The statics quoted by The New York Times is how frequently AVs initiate an RA session. Of those, many are resolved by the AV itself before the human even looks at things, since we often have the AV initiate

proactively and before it is certain it will need help,” Vogt explained.

To manage its mounting costs, General Motors will likely need to secure additional funding for Cruise, according to Chris McNally, a financial analyst at Evercore ISI. During an analyst call in late October, Barra indicated that the company would disclose its funding plans before the end of the year.

Information for this briefing was found via The New York Times and the sources mentioned. The author has no securities or affiliations related to this organization. Not a recommendation to buy or sell. Always do additional research and consult a professional before purchasing a security. The author holds no licenses.